Some time ago, I wrote a piece that outlined what I thought was the sleeper issue of the next Canadian election. Now that the ‘next’ election is now the recent election, it seems like a good time to revisit.

When you look at a political party – any party – you see a monolith. That is, you see a single organization that fields hundreds of candidates across a number of constituencies, either throughout a province or a nation. That is sort of true.

For the main federal “brokerage” parties (to borrow the description from the late political scientist Hugh Thorburn) like the Liberals or Conservatives, you see one party. In reality, there are 344 – the national party and 343 riding organizations.

Political parties in Canada are sort of like fast food chains like McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s or Tim Horton’s. You see a national chain with thousands of outlets, but structurally they are a corporate entity and thousands of independently franchised outlets. Headquarters does not send executive vice-presidents to serve you a double-double from a drive thru window, and the local franchise owner-operator doesn’t do national ad buys or set branding standards.

The same can be said for parties, Local electoral district associations – or EDAs – have a board of directors, fundraising and membership efforts, carry out candidate search functions, coordinate the local nomination, and support the local MP if that candidate wins. Conversely, the national party – like corporate HQ – runs the head office (i.e. Parliament Hill), and through a series of governing documents and regional organizers, enforces standards.

To be clear, like the aforementioned companies, parties will go through some tensions in the relationship. The national organization may piss off the locals by bigfooting - particularly where nominations are concerned. Conversely, the national office lives in dread that the local team in the riding of Lower Podunk-Whosits pulled a stupid that gets traction on CBC, CTV and Global, thereby precipitating the leader / Prime Minister or senior team to engage in damage control for a news cycle or two.

The two live in a polite tension with one another, and this is best represented by the mother’s milk of politics – cold, hard cash.

Outside of an election, the national party and EDA’s are frenemies when it comes to money. That is to say that they target the same people for donations. While I cannot speak to the splits in every party, I have seen it go like this in the past – if a person donates $100 to the local EDA, the local EDA keeps $100. If the national campaign gets the donation, they keep at least $60 and send $40 to the EDA. If you told me that Liberals in Kingston were being encouraged by MP Mark Gerretsen’s people to bogart the Ottawa office and give them the money directly, I would not be surprised.

You’re probably wondering what difference does it make. Well, the national money paid for that pretty Carney 2025 branded bus and jet, and the hotels and meals. The EDA money paid for all those shiny red Mark Gerretsen lawn signs around Kingston, and the wooden stakes that supported them, and the campaign office, and the phones and the internet, and the coffee service, and the gas cards for those who went to the furthest reaches of the riding to put a sign up at 11:45 pm in the middle of a rain storm.

Thanks to our desire not to have US style elections where a billionaire can sink a King’s ransom into a riding or a region, we have limits on donations. Only Canadian citizens and only $1,750 a year. No corporate donations. Even the bank vice-president who earned $15 million in stock options is restricted to that. The only exception is the candidate – but that’s a $5000 limit – not nearly enough to finance a race. The impact of this is that EDA’s run campaigns modestly and on tight margins.

There’s also the spending limit. It’s a function of population and various factors – so it differs from riding to riding - but sticking with Kingston it was $151,724.40. So, every candidate running in that riding can legally spend up to that amount.

So, after thanking you for sticking this out so far, we’re going to get into the nitty-gritty of it all.

Let’s make up a fictitious candidate and party. Fred Smith is nominated to represent the XYZ Party of Canada in Kingston. Fred’s financial agent opens a bank account and the XYZ riding association transfers 90% of its cash to the campaign – the sum of $75,000. From experience, this would be a normal level for a party like the Liberals or Conservatives in a competitive seat.

Well, Fred and his team have a choice – they can be cautious or go all in. This means they decide to either penny pinch and run a modest effort, or they resolve to spend the legal limit. The penny pinch path means spending no more than the $75,000. If their supporters are generous with donations, maybe they spend $85,000. If they let it ride, they spend $151,000.

If they pick the second option, they have a gap of $66,000. To address this they will take out a bank loan.

Why would they do this?

Well, in our system, at the end of the campaign Fred’s financial agent will fill out paperwork and submit it to Elections Canada. In roughly a couple of months, if approved, a cheque will come in the mail. The cheque will be the equivalent of 60% of the writ period expenses. If Team Fred spends $151K, then the cheque should be $90,600. That means Team Fred pays off the $66,000 bank loan and returns the remaining $24,600 to the XYZ riding association. Thus the circle of life is joined, and in 2 to 4 years you lather, rinse and repeat.

Now if Fred was more cautious and spent only $85,000, the rebate cheque would be $51,000 – and after any outstanding bills are resolved the residuals go back to the riding coffers.

The decision to “go big or go home” is one that the locals make based on their risk profile – a combination of past voting trends, the national polls, the “star candidate” factor (if it applies), and so on. It can also be driven by a candidate and campaign manager who convince themselves that they have the next Abraham Lincoln or Winston Churchill in their midst, and that voters will be drawn to them like moths to a bug zapper.

Still with me? Good – now here’s where it gets interesting.

That Elections Canada cheque is either going to be $90,600 or $51,000, except if Fred Smith fails to get 10% of the vote in his riding. If he gets 10.0%, the cheque’s on its way. But if he gets 9.9%? Well, he gets zero, nada, zip, goose egg.

If Fred doesn’t get a cheque, the best case scenario is that the riding association still has the money they held back in the EDA account and they limp along. If they went large, then the riding association loses the money they gave Fred, they will likely lose all the cash they held back, and with absolutely zero funds they will have to contend with angry creditors and a $66,000 bank loan that is racking up interest.

In this worst case scenario, the remedies range from a renegotiation of terms to get an extension, a bailout from the national party, the deregistration of the riding association, and a non-zero chance that the candidate and/or the riding’s board of directors get put on the hook personally.

So how bad a problem is this?

Well, we do not know…yet. The only measure we have are the number of campaigns that fell below 10% on Monday. To truly quantify the issue, you have to know what each of the underwater campaigns started out with, what they spent and what they borrowed (if any). That won’t be known for months – especially if many of the underwater EDAs keep filing for extensions.

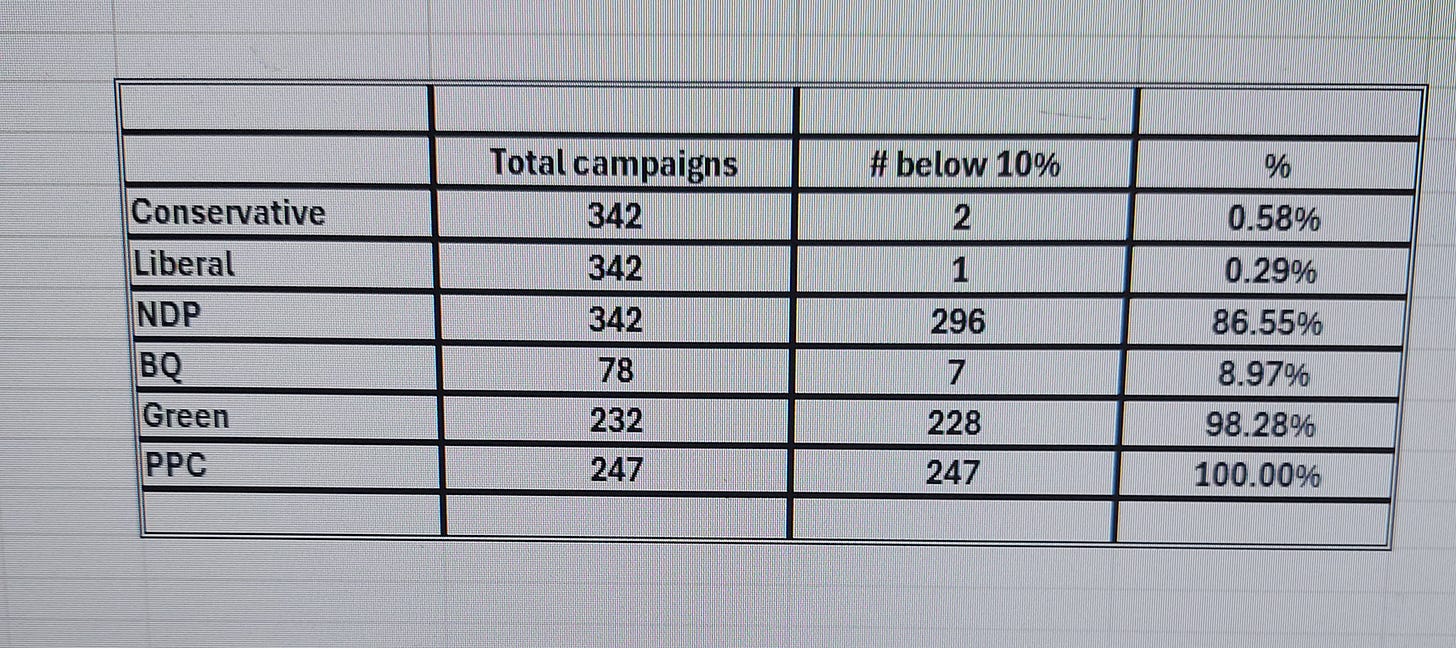

But if we start with what we do know, we begin with this - the BFI, or “Brent’s F—-ed Index,” for the 2025 Vote:

For the Liberals and Conservatives, it’s a relatively simple affair. The Liberals can simply cover the debts in Souris-Moose Mountain (SK), while the Tories cover the shortfalls in the Quebec ridings of Rosemont-La Petite Patrie and Laurier-Sainte Marie. The BQ was underwater in nearly 10% of their ridings, but with 22 seats and official party status, they will no doubt work those out in stride.

The Greens and PPC, despite their numbers, will also limp along – because they ran on the cheap. They have mastered the art of the frugal campaign, and it is likely that outside of Elizabeth May or Maxime Bernier, they wouldn’t have expended much more than the cost of a 52 inch HD television - on sale on Boxing Day. They would open one office for a cluster of ridings, forgo signs and ads, maybe show up at an all candidates debate (or not), and just hope the brand can carry them along. They may have hoped that they could get some bump from the performance of their respective leaders in the televised debates, but their exclusion put that forlorn hope to rest.

That leaves the NDP.

We can guess that the NDP did spend money - because why not? Back when I did this calculation for them in the fall, the underwater number was less than half what we saw on Monday. And they were an official party.

Now, they have lost official party status (and the millions of dollars that helped run their Parliamentary operation), they will have debts associated from supporting Jagmeet Singh – travel, national advertising buys and such – and now they also have to contend with whatever bad debts are coming out of those 296 campaigns that failed to get their 10%. If each of them averages $10,000 of stranded debt, that would be an additional liability of $2.9 million – likely equal to the debt the national campaign incurred.

As I said in a previous essay, this was the Progressive Conservatives in 1993 – but they had three things going for them:

They weren’t this far underwater

They had a trust fund (Bracken Trust) that they could borrow against

They had over 50 Senators who could provide day jobs on Parliament Hill for all those laid off people at Party HQ, who would then spend weekends and evenings volunteering to do the work they used to get paid for.

The NDP lacks these factors, so the road will be difficult. Not impossible, but tough. They still have strong provincial organizations, and governments in Manitoba and BC. Premier Wab Kinew is arguably their single biggest asset. Also, those NDP voters who abandoned their party on Monday night for the Liberals may feel enough buyer’s remorse / guilt for having caused this near-death experience. New leadership and a recalibration back to their Tommy Douglas roots could also help – but the biggest factor will be time.

As for those contemplating a Liberal-NDP merger, that is possible – but I offer a cautionary note. In politics, 1 + 1 is seldom 2. It’s more like 1.2 or 1.4. I saw that with the PC-Canadian Alliance merger of 2003. I can tell you that I know a great number of people who posted on social media that Conservative supporters are Nazis and remember their days as members of Progressive Conservative riding associations and national campaign staff. I am willing to bet $50 that if the NDP merged with the Liberals, a faction led by Avi Lewis or somebody on the left of the party would organize a successor to the NDP for those who disagreed with the marriage.

And do you think Mark Carney’s people want to cover all those stranded debts from the 296 aforementioned campaigns?

Interesting times, my friends – interesting times…